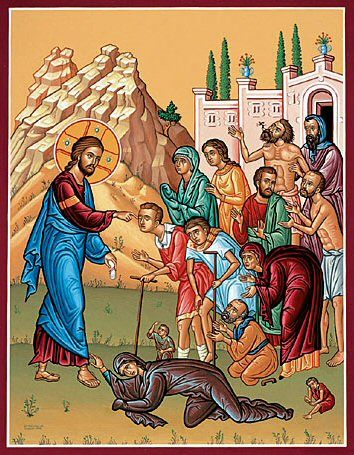

I’m excited to spend the next two weeks preaching exorcism narratives in Mark’s gospel, which communities around the world will be reading this weekend. And so as I’m getting ready to preach these texts, I want to expand on some of my reference points with much more detail than I’ll be able to get into with my sermons.

The main observation I’m making this weekend is, “isn’t it interesting that Jesus performs his first exorcism in a place of worship?”

I think there’s a perfectly cogent and important sermon to be preached there even if we don’t get into the specifics of spiritual geography. Sometimes the influence named and invited to leave is just an ingrained pattern behavior that is destructive to the fabric of beloved community.

The invitation is to pay attention to what stories might be motivating our behavior, and to be honest about them in community with one another, to name the deeper spiritual currents that cause toxic interpersonal dynamics that seem to take on a life of their own, that choke off our capacity to love others as ourselves (e.g., sexism, racism, homophobia), and to firmly ask them to leave. In so doing, we also invite deeper healing to flow into the wounds these powers leave in their wake.

That’s probably as far as I’ll take it on Sunday morning because I don’t want to make people feel weird. I still remember the time at my dad’s genteel suburban United Methodist church when a Baptist guest preacher went on a 45 minute racist tirade about alleged ritual human sacrifice in Africa, and I never want to be remembered for something like that. (That’s a legit aspiration, right?)

But I have a LOT to say about this topic. One, because I find it absolutely fascinating. Two, I have worked in psychiatric settings as a chaplain, in crisis stabilization units and as a job coach for adults with various psychiatric disabilities. I’ll also name that mental illness is part of my ancestral heritage. This has brought me into community and connection with people of various levels of well-being and psychic permeability. And because of that, not only have I accompanied people in the throes of florid psychosis, I have also seen people acting under the influence of malevolent spiritual influences. And they are not the same.

As a spiritual practitioner I am not one to dismiss any narrative of possession simply as a psychiatric pathology seen through the lens of pre-modern culture. In fact, to do so is a move right out of the colonizer playbook, as far as I’m concerned: deny people’s experience, invalidate their epistemological wealth, and flatten their universe into an inert two-dimensional field comprising only resources and consumers? That’s an evolutionary cul-de-sac for the human species, friends.

On this note, I have read multiple sources reporting that in Brazil and other global majority cultures, the treatment of mental illnesses can often a spiritual/ritual component rooted in animist ancestral practice. In these settings, treatment outcomes tend to be much more positive and lasting than in secular Western cultures.

But neither do I swing to the opposite extreme of a neurotic superstition that sees demons lurking in every lingering shadow and popular media franchise. I think this is the same error, just committed in the opposite direction. It’s another manifestation of the story implied by colonizing behavior: “anything that doesn’t gel with my story of the world is to be cast out.”

So how do I navigate this as a person of faith and conscience? Well, it’s taken a little time to get there, but in general, here’s the roadmap I’m working with:

0. Animism is normative human consciousness. This is preliminary to everything else I have to say about this. A secular consciousness that sees rocks, trees, rivers, ore veins, mountains, inter alia as inert, dead matter to be pilfered for resources is a contemporary delusion and a spiritual cancer that is a direct contributing factor to the sixth extinction.

Simply put, animist consciousness views all things as subjects, not objects, and recognizes that all beings have an interior spiritual reality which is reflected outward in a subject’s way of being. For more on this preliminary point, take a listen to this fantastic episode of the Emerald Podcast by Joshua Schrei.

1. Spirits are a thing, and they are real, and an awareness of and respect for their existence is, in fact, part of the Christian heritage.

Rocks, trees, metal veins, stars, animals, and all the rest, as subjects in an animate cosmos, have their own inner spiritual reality and their own way of Being. Origen wrote, “the water springs in fountains, and refreshes the earth with running streams” and that “the air is kept pure, and supports the life of those who breathe it, only in consequence of the agency and control of certain beings whom we may call invisible husbandmen and guardians; but we deny that those invisible agents are demons.”

As well, disembodied intelligences are real, causative agents in the cosmos that also have their own way of Being. Their existence is rooted in finer bandwidth of reality that has variously been called the spirit world, the dreaming, or, in my own tradition’s parlance, the imaginal realm.

Some of its denizens are strongly differentiated with distinct personalities. Some of them are like the little bits of mold that grow on bread forgotten at the back of a cabinet, just vibing and playing their part in the becoming of things.

On that note, I am convinced that the Constantinian tendency in ecclesial history to regard any other spirit, intelligence, or other such being outside of the Church-approved roster of saints and angels as demonic and evil is foolish and does real harm to people and to cultures.

This tendency has borne out in our tradition’s sad and storied history of colonization, forced conversion, desecration of sacred sites, and other acts of cultural genocide perpetrated in Christ’s name in the last 400 years alone. (Origen was right!)

These beings all have their place in the cosmos, for anything that exists receives its existence from the life of God, and exists to show forth some hidden beauty coiled in the divine heart. As Gregory of Nyssa says in praise, “all that is prays to You.”

2. They are not all evil.

Just as the visible world is populated with all different shapes and sizes and qualities of being, so is the imaginal realm. The vast majority of them are morally neutral and completely disinterested in the affairs of humans, as separate from us and our concerns as nascent galaxies on the other end of the universe.

Many are so big and so immanent as to become reference points for the operation of human biology and consciousness (the sun, the moon, the planets and stars, for example).Others among them accompany particular peoples, places, and cultures as Big Powers and protecting presences, with whom we as conscious beings in the visible world can justly seek right relationship as neighbors.

Some of them are simply “unclean,” which (in my view) does not mean that they are ontologically evil, but rather that they act like hungry parasites, absorbing the energy of the ones to whom they have become attached. Some of them are simply predatory in the way a lion is; morally neutral, but they gotta eat.

Some of the denizens of the imaginal realm are powers that we ourselves generate in the chaos of our own psychological ferment, ideas and images that take on a life of their own. And some of these entities are malevolent, ancient, cunning, insidious, and destructive forces that enslave us to their worship and consume us from the inside out.

But know that these are the subtlest of all.

3. You [or your loved one or your enemy or a person struggling with mental illness] are probably not possessed.

While the influence of malevolent spirits can often manifest in acute forms such as we see in the classic exorcism narratives and in Hollywood, they are often much more subtle. Most of us will never experience or witness an acute possession, thanks be to God. Nor are the Powers that enthrall and destroy necessarily ancient demons with unpronounceable names.

We experience their influence most readily through the inner spiritual realities at the heart of our institutions, with perfectly accessible names like “ExxonMobil” and “Raytheon” and “The United States of America” and even “Money,” which is why I always refer to these as “the Powers that Be.” And to be sure, these powers absolutely do make their influence known through the channels feared by fundamentalists: through culture, through commerce, through media, through the stories they whisper to willing listeners to curry our brand loyalty.

And yet, powers like these are hardly at the top of the food chain; they are the faithful devotees of the ancient powers of Greed and Craving and Fear themselves, powers which could only be born in the minds of humans to begin with.

Isn’t it interesting how that which lives within us has its correlates in the world outside us? That’s a whole other essay.

4. A Christian ethic, working in an animate consciousness, demands that we endeavor to be in right relationship with our more-than-human neighbors, including the bodiless Powers. Animist consciousness helps us develop the discernment and skill necessary to name these consumptive, destructive powers for what they are, to sense and call out the subtleties of their influence on individuals and communities, and to call upon the Big Powers to effect our liberation from the same.

In this, St Paul was right when he said, “For our struggle is not against enemies of blood and flesh, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers of this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places” (Ephesians 6.12).

Here’s where my Christian bonafides meet into my animist existence: I don’t believe this struggle is a question of destroying these powers. They have already been defeated by the Human One. As such, I believe we are called to work toward their redemption and rehabilitation as part of the general ministry of reconciliation to which humanity has been called in Christ as we participate in his work. Sometimes that redemption is so thoroughgoing a transformation that the power (or person) in question is unrecognizable afterward (Walter Wink makes this precise point in The Powers that Be, which is a favorite text of mine).

Further, animist consciousness helps us that we can recognize and relate to these powers as subjects, not objects. That means that we can, and must, learn to set boundaries with them. Sometimes being in right relationship to our spiritual neighbors in this world means having incredibly firm boundaries and expectations with them, for the sake of communal well-being.

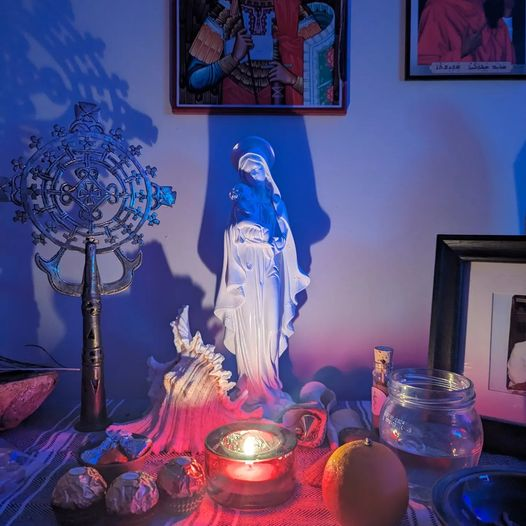

Ritual protocols help us do this. Energetic hygiene helps us do this. Caring for our bodies and our relational health with other humans helps us do this. Nurturing the mythic consciousness through story and song, that layer of human experience which emerges from the animate, helps us do this. Setting timers on our phones so we don’t lose ourselves in the quagmire of social media discourse helps us do this.

5. As long as humans have interacted with the imaginal realm, we have been developing tools and technologies to navigate it and relate to its denizens conscientiously. Many of these protocols are cultural and ancestral skills that contemporary society has lost touch with, either as a result of the colonization of culture by post-Christian secularism or the interruptions in their transmission caused by cultural trauma.

Yet, thanks to the contemporary media landscape and an economy of ideas unprecedented in human history, fortuitously, many of these skills are also finding their way back into the hands of practitioners and ordinary folks. Even contemporary psychiatric medicine is beginning to make more and more room for the implications of an animate cosmos in its treatment plans as we move away from a model of the human being as little more than a complicated wad of machinery and hormones.

As we move through this world as people in pursuit of justice, wholeness, and peace, we will doubtless find ourselves in situations where we have to name a destructive spiritual influence and see through it and all the chaos it causes to the person held within. We do so under the authority of fellow citizens of an animate cosmos. We do so under the authority of our own spiritual existence.

And, indeed, for those of us who follow the Way, we do so under the authority of the One upon whose breath moves all breath, whose Spirit speaks all Beings into being. So get out there and name some powers. Call them out. And while you’re at it, seek to be in right relationship with all your neighbors, not just the human ones, not just the physical ones. (And I guess that’s the sermon.)

…

If you want to read more on this, the theologian Walter Wink comes closest to what I would consider an accessible animism among mainline theologians, and his book “The Powers that Be” is one of my favorite reads. I’ve also found the work of Dr. Daniel Foor, Kabir Helminski, and Dr. Cynthia Bourgeault on these areas to be extremely helpful. Joshua Schrei at the Emerald Podcast is doing wonderful work to make this way of seeing more bio-available too.

But beyond that, much of my thought on this has also been formed by my lived practice engaging the animate world in day-to-day practice, as well as my own experiences in different states of consciousness, my reading of the Christian tradition in dialogue with other traditions that have maintained their animist, ancestral, earth-honoring roots, and the faculties of spiritual perception that contemplative practice cultivates.

As a bit of a post-script: the easiest way into animate consciousness is simply to start saying “thank you” to every thing with which you interact. Wash your hands? Thank the water, the faucet, the soap, the people who shipped the soap, the dinosaurs and plants whose bodies decomposed into the oil that was turned into the gasoline that fueled the creature of metal and fire that drove the soap to the store… and just keep going. Do that for a week and see what it does to how you see the world. May the spirits find you in right relationship.

teaching deconstructs prevalent notions of family that existed in the Greco-Roman world and persist to today. God’s reign does not only bring shalom to heteronormative middle American nuclear families, but to those of us whose families look a little weirder than normal.

teaching deconstructs prevalent notions of family that existed in the Greco-Roman world and persist to today. God’s reign does not only bring shalom to heteronormative middle American nuclear families, but to those of us whose families look a little weirder than normal.

You must be logged in to post a comment.